By Jesse Bogan

St. Louis Post-Dispatch

(TNS)

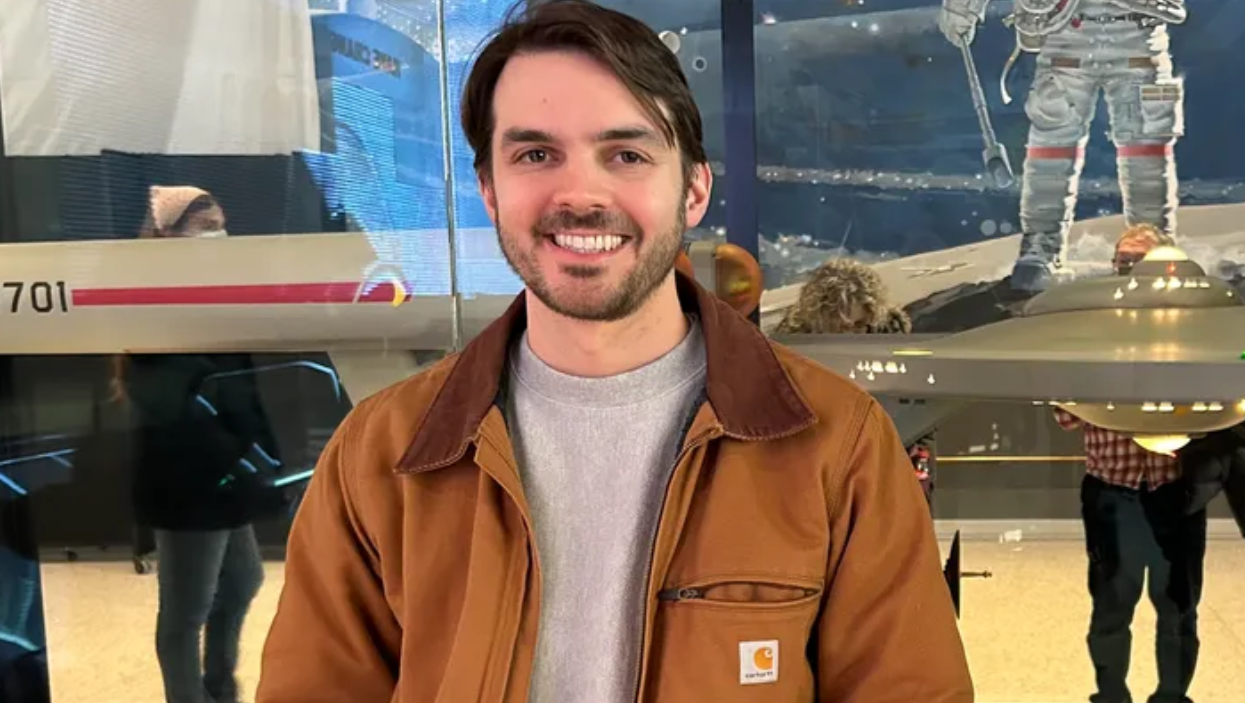

ST. LOUIS — Charles E. Littlejohn wasn’t alive when Crossroads College Preparatory launched in 1974. Yet he embodies the founding spirit of the small private school in the DeBaliviere Place neighborhood.

Smart guy. Aware of the forces at play in physics and politics. Not only can design and solve multi-step problems with the latest technologies, but he’s willing to take a stand for what he believes is right for the greater good of society.

You’d think he might be a go-to staffer on Capitol Hill.

Instead, he’s inmate No. 96530-510 at the federal prison in Marion, Illinois.

“I am really impressed with what he did,” said Arthur Lieber, 77, who co-founded Crossroads. “Whether you agree or disagree, he was in a very difficult position. He seemed to do something that was very courageous.”

Littlejohn, 39, pulled off what’s been described in court as the greatest heist in IRS history. As a contractor for the federal government, he stole President Donald Trump’s tax returns—so sought after that they were locked up in a vault for protection—and leaked them to The New York Times.

It wasn’t another rash decision for riches that leads so many others to incarceration. The first-time offender had a “deep, moral belief” that sharing the information with fellow Americans “was the only way to effect change,” his attorney argued.

Even with a job that granted access to unmasked taxpayer data, his crime took a couple years to commit. He needed access to the data. He needed to cover his tracks. And he needed to be sure, all things considered, that stealing records from one of the most mercurial presidents in U.S. history was the right thing to do.

In 2020, a little over a month before the Election Day showdown between Trump and Joe Biden, the Times published damning details of the findings. The report came with a note from Editor-in-Chief Dean Baquet:

“Every president since the mid-1970s has made his tax information public. The tradition ensures that an official with the power to shake markets and change policy does not seek to benefit financially from his actions. Mr. Trump, one of the wealthiest presidents in the nation’s history, has broken with that practice.”

Indeed, Trump tried to hide filings from the public that showed he paid just $750 in federal income taxes in 2016—the year he narrowly beat Hillary Clinton for the presidency—and didn’t pay any income taxes in 10 of the previous 15 years.

“The records show a significant gap between what Mr. Trump has said to the public and what he has disclosed to federal tax authorities over many years,” Baquet added. “They also underscore why citizens would want to know about their president’s finances: Mr. Trump’s businesses appear to have benefited from his position, and his far-flung holdings have created potential conflicts between his own financial interests and the nation’s diplomatic interests.”

To Trump, it was another example that the press is an “enemy of the American people,” the mouthpiece of the left.

While the leak caused a sensation, outcry from both sides of the issue soon shifted to the Jan. 6 uprising that tried to block the certification of electoral votes by Congress.

But by then, Littlejohn had already doubled down. He anonymously leaked a “vast cache of IRS information” to ProPublica that showed the wealthiest Americans pay relatively little in federal income taxes. The nonprofit national news outlet would go on to publish numerous stories.

To some progressive readers, the details raised questions about a possible wealth tax. To some of the people who were exposed, ranging from Elon Musk, the richest man in the world, to U.S. Sen. Rick Scott, R- Florida, one of the wealthiest members of Congress, it stoked outrage.

When Littlejohn was finally discovered, he didn’t run. He cooperated with prosecutors from the U.S. Department of Justice’s Public Integrity Section who wanted to know what else had been leaked. They wanted to know how he committed the “unparalleled” crime. Trump had an opinion about that. In court, his attorney accused Littlejohn of being a “CIA asset” who worked for the same firm as Edward Snowden.

In October 2023, avoiding trial, Littlejohn pleaded guilty to one felony count of unauthorized disclosure of income tax returns. Republican leaders described it as a sweetheart deal and the judge seemed to agree at some level. She repeatedly questioned prosecutors about why they hadn’t charged Littlejohn with additional crimes that would bring more severe penalties.

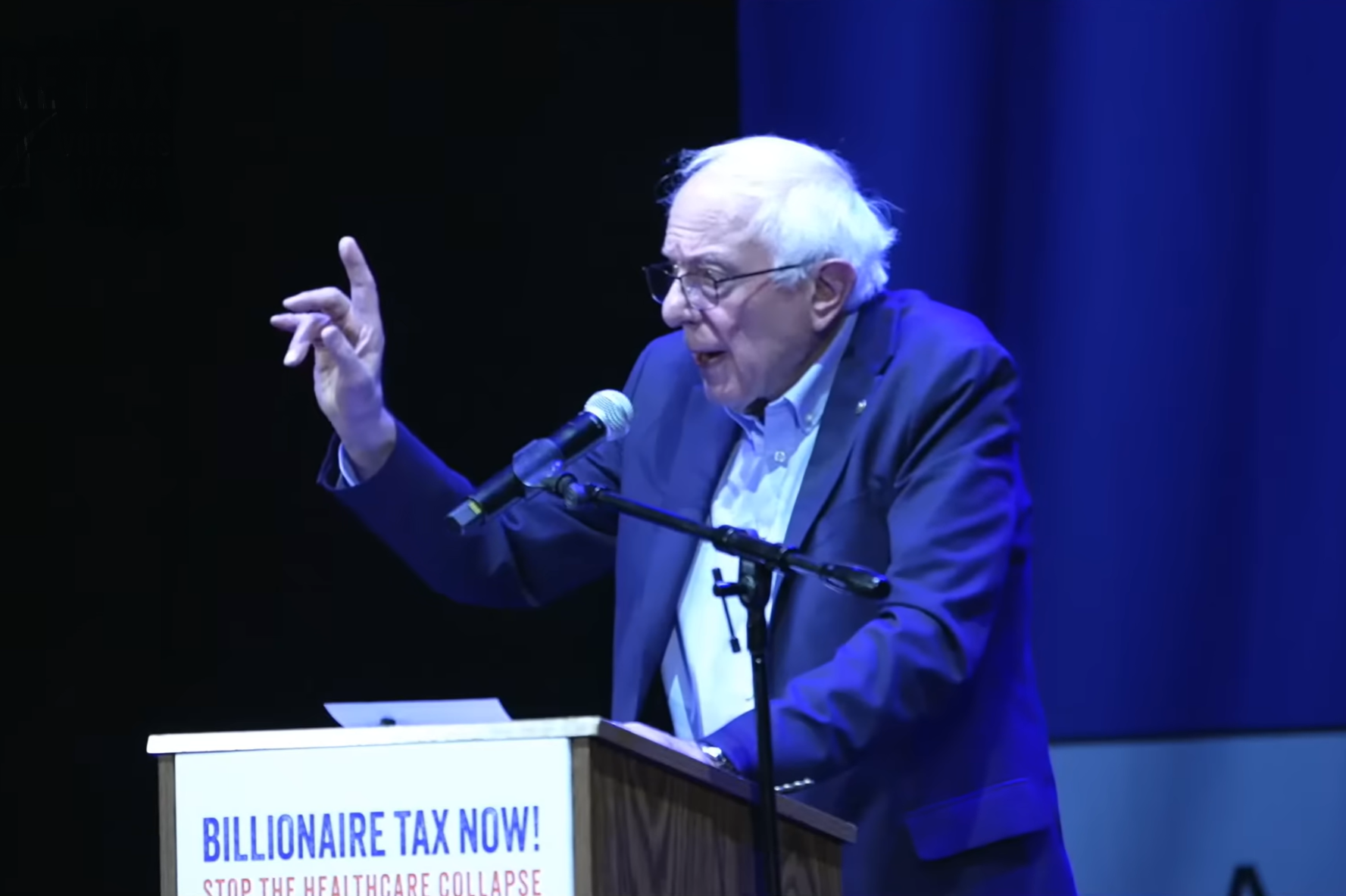

Still angry in January, Scott came over from the Senate to provide a victim impact statement at Littlejohn’s sentencing hearing in the U.S. District Court in Washington, D.C. Scott, who has long since rebounded from being forced to resign as CEO of a for-profit health care firm that paid $1.7 billion in fines after a federal fraud investigation, asked the judge to issue the maximum sentence.

“In a broad sense every American is a victim here,” Scott, who also has roots in Missouri, told the court. “Why? Because this case is part of the ongoing dangerous corruption of the justice system at the federal level.”

The company you keep

Court records and interviews with people who know Littlejohn signal that he’s a principled deep thinker. Not overly political, but informed and the kind of friend willing and able to step up and officiate a wedding.

“He’s an extremely intelligent man,” said Kathy Peterson, a retired educator from St. Louis whose children attended Crossroads with him. “He’s extremely thoughtful.”

After high school, he studied physics and economics at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, graduating summa cum laude. One family that still remembers him there said Littlejohn’s group of friends volunteered their computer programming skills at a few charities.

“He has very altruistic goals for himself and his life and his community,” Diana Monroe, in her 70s, said by telephone from Durham. “A lot of it has to do with his upbringing. A lot of it has to do with the friends you make over time.”

Grief also seems to be at play.

Around 2012, Littlejohn took a break from working as a government contractor in D.C. to support his family and teenage sister in St. Louis after she was diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia. Littlejohn wanted to help by donating bone marrow, court records say. Though he wasn’t a match for her, Littlejohn donated his marrow and T-cells to an anonymous cancer patient on the registry for two years.

His sister beat leukemia but died from an antibiotic-resistant infection. She was 19. According to her obituary, she’d graduated near the top of her class at Crossroads and was headed to Emory. She’d spent much of her senior year in the hospital.

Littlejohn tried to prevent other families from being devastated by something preventable. In an online posting, Pew Charitable Trusts recognized Littlejohn and his father as notable advocates gathered in Washington who urged for “sustained funding to combat antibiotic resistance.”

After studying history at Harvard and Cambridge, and business in Pittsburgh, Littlejohn’s father worked in communications for several large companies in St. Louis. Littlejohn’s mother is a lawyer on the speaker circuit. His parents divorced and remarried when Littlejohn was young. Neither responded to requests for comment.

In 2017, back in D.C., Littlejohn relocated again to support family. This time to Delaware to help care for his dying grandfather, a decorated World War II veteran, who also helped fly cargo to troops in Korea and Vietnam. Around the time of his grandfather’s death, Littlejohn sought his former position as a contractor for the IRS with the goal to take the president’s tax records, according to his plea agreement.

Prosecutors said Littlejohn accessed the records in question on an IRS database by using broad search parameters “designed to conceal the true purpose of his queries.” To further avoid detection, officials said he uploaded the information to a private website and saved the tax returns to multiple personal storage devices, including an iPod.

Prosecutors said he first uploaded Trump’s tax returns around Nov. 30, 2018, and didn’t start disclosing them until months later. He continued to share more of Trump’s private tax information in 2019, as well as in 2020.

Also in 2020, a close family friend of Littlejohn’s died of cancer. He wrote in his journal the next day about the young woman: “Life is so fragile and short. Grieving for the years she will not see the friend[s] and family that will carry her loss for the rest of their days. We should all try to live our lives as if we will die tomorrow.”

The following week, he contacted ProPublica with a much bigger trove of stolen tax data about the wealthiest Americans.

What would Marcus Aurelius do?

U.S. District Court Judge Ana C. Reyes, a Biden appointee born in Uruguay, wasn’t impressed by Littlejohn’s prowess.

She said from the bench that she’d sentenced six people involved with the Jan. 6 uprising. None got prison time. Those defendants, Reyes explained, got caught up in the moment, whereas Littlejohn “carefully planned” actions that were “also a threat to our democracy.”

“I have reacted so strongly to your case,” Reyes said. “It engenders the same fear that January 6th does, that we have gotten to a point in our society in which otherwise law-abiding, rational people believe that they have no choice but to break the law to further their political agendas.”

She said the Founding Fathers of the United States warned about the “corrosive effect” of lawlessness on society. She went deeper, to Socrates, the ancient Greek philosopher and founder of the Socratic method. Out of integrity, Socrates chose not to escape prison to avoid death in 399 BC for his crimes of impiety and corrupting the youth.

“Socrates argues that the duty of the citizen is to obey the law or persuade society that the law is wrong,” Reyes said.

Reyes said she didn’t care how many people might agree with what Littlejohn did.

“When you target the sitting President of the United States, you are targeting the office,” she said. “When you target the office of the President of the United States, you’re targeting democracy. You’re targeting our constitutional system of government.”

In his prepared remarks, Littlejohn apologized. To the court. To the government. To Sen. Scott and everyone else who has been hurt.

“I alone am responsible for this crime, and I received no compensation in return for committing it,” he said. “I acted out of a sincere if misguided belief that I was serving the public interest. … I believed then, as I do now, that we as a country make the best decisions when we are all properly informed.”

He said he understood that what he did was illegal and “caused significant harm.”

“In deciding to disclose this information I was aware of the potential consequences,” he said. “I did not take the burden of this obligation lightly, nor did I think I was above the law. I made my decision with the full knowledge that I would likely end up in a courtroom to answer for my serious crime.”

What he did was wrong, he said.

“I used my skills to systematically violate the privacy of thousands of innocent people,” he said. “My actions undermined the fragile faith that we place in the impartiality of our government institutions.”

No mercy, he asked, just justice.

“It alone can help restore confidence in our system,” he said.

As for himself, he said, he would reflect on a passage from Meditations, the book written by Marcus Aurelius, the stoic philosopher believed to be the last of the “Five Good Emperors” of Rome.

“Never regard as a benefit to yourself anything which will force you at some point to break your faith,” Littlejohn told the court. “My hope in moving forward from this experience is that I will be able to internalize that message as I seek lawful ways to contribute to my community and to our beloved country.”

The judge said everything Littlejohn exposed could have been figured out and dealt with legally and that the “arena for the strongest expression of our political beliefs is the voting booth.”

Then she sentenced Littlejohn to the maximum: five years in prison, with an additional three years of community supervision and 300 hours of community service. He was ordered to pay the maximum fine of $5,000.

“You can choose to let this chapter of your life define you as a failure, or you can choose to let this chapter propel you to a better version of yourself,” the judge told him.

‘Smart + Good’

Littlejohn started serving his sentence last spring. Per his request to be close to family in St. Louis, the judge allowed him to be placed at the federal minimum-security prison camp in Marion.

He declined an interview request from the Post-Dispatch. His federal public defender didn’t respond and the lead prosecutor in his case declined to comment.

Records show that Littlejohn is appealing his sentence. Meanwhile, strong editorials have surfaced in publications like Slate and Rolling Stone calling on Biden to pardon Littlejohn. A tax attorney asks in Forbes if whistleblower protections should be expanded in cases like this one.

Some of his supporters are worried what will happen if Trump wins. Just a few weeks before the Nov. 5 election, he and Vice President Kamala Harris are in a tight race. At a recent rally in Pennsylvania, a battleground state, Musk, the richest man in the world, jumped for joy stumping for Trump.

More than 650 donors have contributed nearly $56,000 to a GofundMe account created to help cover Littlejohn’s legal bills. Many of the names are anonymous. Not Lieber’s, though.

He said Littlejohn reflects the spirit of the early years of Crossroads. He said he cofounded the small private school in his 20s with a sense of immediacy after teaching in the St. Louis Public Schools system.

“We’re impatient people,” he told the Post-Dispatch in 1980 when Crossroads expanded to include the only nonsectarian private high school in the city at the time. “We are not the kind to work for years within the public school system until we got enough seniority to be able to make changes.”

Lieber went on to found Civitas-STL, a nonprofit still involved with Crossroads that trains youths to be active citizens. Not one to just lecture, Lieber said he ran for Congress in 2010 and 2014 when no other Democrats stepped up. He vowed to accept little or no campaign contributions. Education was another bullet point in his campaigns: “We need schools that value the common good; that recognize that our country can be governed much better; that see that their primary role is to help students learn critical thinking skills and apply them for the benefit of society as a whole.”

Republicans Todd Akin and Ann Wagner beat him by landslides.

But Crossroads, grades 6-12, continues its experiment in the city with an enrollment of 120 and a 6:1 ratio of students per teacher. A large mural on the building shows a diverse mix of students. One holds a sign that says “Smart + Good.” Another wears a red COVID-19 mask with the word “Empathy” drawn across it. A colored rack of books—lit, math, science and history—stands beside a batch of balls.

There is a no-cut policy for sports teams. In recent years, an AP literature class explored banned books.

Current leaders at Crossroads didn’t respond to a request for comment about Littlejohn. Last month, Rachel Kristy, a 1989 graduate of the school, attended the 50-year anniversary celebration of Crossroads. She said no one spoke to her about Littlejohn. She’d never heard of him but wasn’t surprised he’d gone to school there.

She recalled an urban exploration class she had at Crossroads. One night, they camped out in a parking garage at the old Busch Stadium to learn what life in the city was like long after the Cardinals games were over.

“We got to see what made the city tick a little bit,” she said.

Kristy, 53, a technical writer based in the Washington, D.C., area, said a lot of alums are informed and motivated to act. She said many of the graduates became defense attorneys who dedicated their careers to a more equitable criminal justice system.

“They just did it within the boundaries better,” she said.

________

(c)2024 the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Visit the St. Louis Post-Dispatch at www.stltoday.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency LLC.

Thanks for reading CPA Practice Advisor!

Subscribe Already registered? Log In

Need more information? Read the FAQs